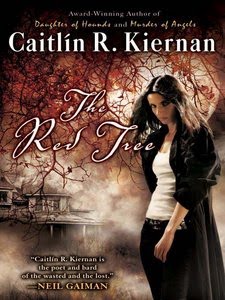

The unreliable narrator is a pretty common concept, one that lends itself to telling scary stories, but rarely do I see it employed as wonderfully as Caitlin Kiernan does in The Red Tree. The way the book is set up treats it like a “true story”—it opens with an “editor’s note” about Sarah Crowe’s final manuscript, the journal that is the text of The Red Tree. From the start, the reader is aware of the fact that these are the writings of a woman who has killed herself and who was haunted by increasing delusions and hallucinations (or so the editor tells us, so we must suspect). However, when you’re reading the book, you believe. You believe until the last moment when you realize that all has not been as Sarah told you, and then it’s fabulous to go back and re-read that “editor’s note” at the beginning. There is no way to know for certain what really happened to Sarah or around her, and what was in her head. Not only is her mind unreliable, but the text is organized as a journal she herself kept and edited. A dual-layer of unreliability and shadow lurks in those words—what lies was she telling herself, or what polite fictions to hide her own agony?

Underlying the potentially supernatural horror story is the “real” horror story of a woman whose lover has committed suicide and who cannot form another meaningful connection with someone. Sarah’s sexuality is a major point in the book, but not solely because she’s a lesbian. It’s important because of how much love has damaged her by the point in which she’s writing the journal at the farm. The way Kiernan balances the supernatural ghost stories of the red tree and its grisly supposed past against the reality of a woman with slipping sanity is masterful. The question of which story is “true” might be irrelevant, here, though—both were true to Sarah, despite the moments in the text she seems aware that she might be imagining things or losing her grip.

Really, a large part of me just wants to hit the caps-lock button and write “buy this buy this buy this,” but I have more to say than that. However, keeping back the flood of glee over how much I enjoyed this book, from the narrative construction to the story itself, is difficult. Kiernan’s skill is impossible to deny after reading The Red Tree. As a reader and a writer I felt like I had read a masterpiece when I finished and re-read the first chapter (of sorts). The way Kiernan uses words to make Sarah real is something that requires a deft and delicate hand. The journal has intentional “errors” in it, repetitions of words or the regular digressions Sarah herself acknowledges, that make the experience even more real. When absorbed into this narrative, you feel that you might actually be reading the last manuscript of Sarah Crowe. That’s something many people who write “journals” miss—when someone, even a professional writer, is keeping a journal, it is going to have rough edges. Nobody spends time polishing the prose in their journals, really. Yet, even those rough edges manage never to be bad writing because they’re done with so much care. (I could go on about how pretty the words are in this book, but I’ll try to refrain.)

Sarah Crowe is one of those narrators who is a mystery wrapped in an enigma, willfully hiding things from herself and the reader but never for a petty reason and never in a way that will frustrate you. It’s interesting to consider how much her sexuality might have informed her personality and her writing as we see it in The Red Tree. She has a deep-seated insecurity that eats away at her, a self-hatred that eventually leads in some part to her death, and the feeling that she cannot be worthwhile for another person. She grew up in a small town, a fact that she circles and circles in the text—which seems to indicate that she can’t get her past there out of her head. The fact that they removed her books from the library there is another indicator. She didn’t belong, and really, I feel like she never thought she did, no matter where she went. That could be because of other social anxiety issues or her sexuality or both; I appreciate that Kiernan doesn’t use her sexual identity as a cheap drama-chip. It’s handled with class, realism and style.

As for her relationships, the cloud over the whole book is her problematic one with her dead lover, Amanda. Amanda cheating on her was enough of a betrayal, but then she commits suicide, something Sarah seems unable to move past. She can hardly talk about it, even in her journal. I did relish the way their relationship and sex in general was treated in this text. Sarah uses sharp language and has frank sexual desires that she isn’t afraid to talk about. Too often in fiction, it seems like lesbians are handled as ultra-feminine people who think about sex in terms of snuggles. I love it when an author frames desire for a woman in a way that rings true for me: it isn’t always soft and sweet. It’s sex, it’s physical, and it’s often raunchy/filthy/rough. It’s not all about snuggles and cuddles, especially not a one-night stand. Some readers might not get the same mileage out of Sarah’s descriptions of sex, because she can be rather caustic and demeaning when thinking about other women. However, I’d argue that’s because of her position at the time she’s writing the journal—she’s been dreadfully hurt by someone she loved with too much passion, someone who she can never even say goodbye to, and love to her is an ugly, raw topic. All of that self-hatred doesn’t circle around sex or sexuality, but I’d say at least some of it does, and that comes through in her language. Her relationship with Constance is one of the debatable portions of the book: we know from the editor’s note that Constance really was there for some time, but not when she actually left and not if they really did have sex. Sarah believes they did and is bitter about Constance’s cavalier attitude about their encounter, but it’s interesting to consider the fact that it may not have actually happened. If not, is the imagined encounter an extension of Sarah’s confusion of Amanda with Constance? So much of the novel is completely unreliable, it’s hard to say. The way trauma can manifest itself in dreams and desires is something Kiernan uses to full effect in this story.

I like Sarah. I love how Kiernan writes her, and has her write. The closeness of mental illness and writing in this text are uncomfortable but in a good way. Sarah is a woman carrying around open wounds that she’s not very good at hiding, from her perceived failure as a writer to the loss of her lover. Her voice is full of that pain but so engaging, up ‘til the last page. The tangled threads of reality and mythology, life and dream, death and love—they all weave together in The Red Tree. It’s not just a book of queer SFF. It’s an absolutely excellent book of queer SFF that I would recommend to any reader, even one who isn’t directly interested in issues of gender and sexuality. The story manages to be so many things at once, from personal narrative to ghost story to nearly Lovecraftian horror to historical record of the red tree itself. It’s gorgeous, it’s certainly scary, and it’s worth laying hands on if you have the chance.

Lee Mandelo is a multi-fandom geek with a special love for comics and queer literature. She can be found on Twitter and Livejournal.